The National’s Bryce Dessner’s Classical Gas (Interview)

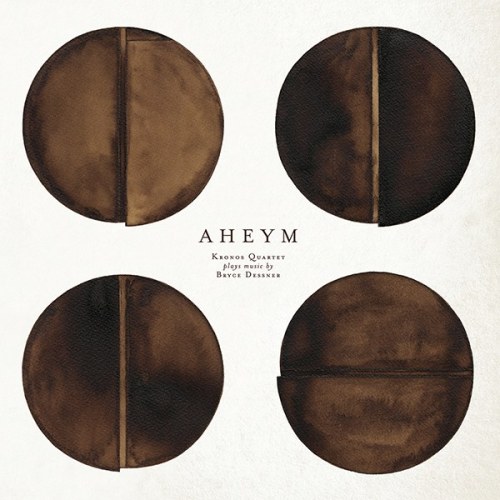

In addition to his duties as guitarist for The National, Bryce Dessner is an accomplished classical composer. Armed with a Master’s Degree in Music from Yale University, Dessner has composed four pieces for the Kronos Quartet. Those four pieces make up the album titled, Aheym, which has been released by the Anti- label today. The 13th Floor spoke to Bryce Dessner prior to the album’s release and asked him to discuss each of the four tracks included in Aheym in depth. He was happy to do so.

Listen here to the interview with Bryce Dessner:

Read a transcription of the 13th Floor interview with Bryce Dessner here:

Marty Duda: So my understanding is that the title track is actually the first work that you’ve written for a string quartet in particular, so I was hoping you could give me a little insight—

Bryce Dessner: Yeah, I had written a previous work to that that was string quartet and guitar, and it’s a piece called Quintet, it’s kind of a big piece, but Aheym is actually my first string quartet.

MD: Is that a daunting task? How different is it for you than what you normally write, and how did you have to approach it?

BD: I mean, I have a really long background in contemporary music and composing in general, and I’ve done a fair amount for strings, so in a way it was kind of a natural evolution, but writing for string quartet is a very particular kind of thing. It’s such an amazing… it’s one of the great archetypes of classical ensembles, there’s obviously all this incredible repertoire written for it. But it is difficult because it’s very bare – you know, everything is heard. It can be a very unforgiving kind of medium. So in a way it’s harder than writing for a mixed ensemble or even larger forces like a string orchestra or orchestral chamber orchestra – that kind of thing can be easier, in a way, than a string quartet, which just requires real… every part has to be really dynamic.

So it was a challenge, yeah, the first one was Aheym, and that piece was written for a really specific situation, where they were playing an outdoor concert in New York and they commissioned me to write this piece, it was a concert at the Prospect Park which is about three blocks from where I live. So it was kind of a lot of pressure because Kronos is really America’s most famous contemporary string quartet and then they were gonna do it in front of five thousand people in my home town. Not far from me. So it’s like playing a new piece of music in front of all of my friends. It was a bit of pressure, but it also specifically– David Harrington, is really the kind of artistic director of the group and the founder and really amazing person; he was really helpful in directing me and said, you know, ‘you probably don’t want to make it too quiet or too subtle’. Which is why what came out of that is this pretty ferocious string piece that they’ve gotten on to. I expected them to play it once or maybe twice, but it’s become kind of a permanent part of their touring repertoire so I think they’ve played it over a hundred times since then… which is kind of amazing. In a way, it’s like I managed to strike a nerve of what type of music they, at that time, they wanted in their repertoire or something. So it’s a piece that really features them and it kind of pushes the limits of what’s possible, it’s technically very difficult. It’s kind of woven out of these simple fragments and rhythms that repeat and there’s a kind of kinetic energy about it, and I wanted to do something that was pretty tightly wound like that. And then from there, the other pieces were in a way written in response to it, because I had done this thing that had been at least successful as far as they were concerned. So I was kind of wanting to explore other types of writing and material for the other works on the record.

So it was a challenge, yeah, the first one was Aheym, and that piece was written for a really specific situation, where they were playing an outdoor concert in New York and they commissioned me to write this piece, it was a concert at the Prospect Park which is about three blocks from where I live. So it was kind of a lot of pressure because Kronos is really America’s most famous contemporary string quartet and then they were gonna do it in front of five thousand people in my home town. Not far from me. So it’s like playing a new piece of music in front of all of my friends. It was a bit of pressure, but it also specifically– David Harrington, is really the kind of artistic director of the group and the founder and really amazing person; he was really helpful in directing me and said, you know, ‘you probably don’t want to make it too quiet or too subtle’. Which is why what came out of that is this pretty ferocious string piece that they’ve gotten on to. I expected them to play it once or maybe twice, but it’s become kind of a permanent part of their touring repertoire so I think they’ve played it over a hundred times since then… which is kind of amazing. In a way, it’s like I managed to strike a nerve of what type of music they, at that time, they wanted in their repertoire or something. So it’s a piece that really features them and it kind of pushes the limits of what’s possible, it’s technically very difficult. It’s kind of woven out of these simple fragments and rhythms that repeat and there’s a kind of kinetic energy about it, and I wanted to do something that was pretty tightly wound like that. And then from there, the other pieces were in a way written in response to it, because I had done this thing that had been at least successful as far as they were concerned. So I was kind of wanting to explore other types of writing and material for the other works on the record.

MD: So I was hoping you’d touch on some of the other ones as well. There’s four pieces in all, and they’re written over the course of a period of time from 2009 to last year as I understand it, is that right?

BD: Yeah, so Tenebre is the second piece I wrote for them and that’s the longest piece on the record. And that one– like I said, Aheym has a kind of economy about it, whereas it’s really a fairly—you know, the language is tightly wound and it has almost like a rock energy to it. With Tenebre that was also commissioned for a certain set of circumstances. It was commissioned by Kronos as a birthday present to their lighting designer, to a guy named Larry Neff, who had been with the ensemble for 25 years, and it was his 50th birthday. So Kronos basically chose me to write a piece for him, which I thought was a very beautiful dedication, that they wanted to commission a piece for someone in their organisation. It was also to premiere as part of the celebration of Steve Reich’s 75th birthday who originally is the reason why I know Kronos, because I’ve worked with Steve Reich over the years and then obviously Kronos has been really really a big champion of his music. So it was this double-edged sword of doing stuff for the Reich weekend in London – at the Barbican is where it premiered – and also writing this very personal piece.

Tenebre also has a kind of specific inspiration, and I was looking in– he was for the lighting director in Kronos, right, so I was kind of investigating the relationship between light and music, and did all kinds of different– usually when I write these pieces I’ll do research to sort of find a direction or some idea behind it, and in this case Tenebrae is a Holy Week service. It’s part of Maundy Thursday; it’s the Thursday before Good Friday. Specifically what’s interesting about it is that they extinguish 15 candles in the church throughout the mass into darkness, and it’s to symbolise the death of Christ. And you know, I have a Jewish background and so it’s not necessarily that my piece… it has no kind of religious connotation, but what I did do is I referenced all this incredible Renaissance music, Renaissance and Baroque music that was written for that mass. So things like Couperin and Tallis and Gesualdo and Victoria… and there’s all this incredible music that was written for Tenebrae, so I was kind of studying it as music that’s meant to kind of score this idea of light to dark. There’s references to some of that music in the piece, and then I also kind of built it formally around the structure of the mass.

The other really interesting thing, and this maybe gets into the influence of Steve Reich a little bit, I don’t know if you know but Steve is an orthodox Jew who does have some kind of religious references in his music, so I thought it could be interesting to have a kind of subtle nod to that, in that the Tenebrae service is one of the few in the Judeo-Christian tradition where at the actual beginning of the mass they sing the Hebrew alphabet. So the composers would set these long melodies on the actual Hebrew letters. So that’s what you get at the end of my Tenebre, so the piece is kind of woven and inspired out of this vocal music of the Renaissance period, and then at the end you actually hear voices that sing the alphabet, so you hear the first seven letters of the alphabet. So that was that kind of inspiration for the piece. I would say that, like I was saying before, that it was kind of a response to Aheym, with the first piece, and that Tenebre is formally more ambitious, it’s longer, it has more colours, more subtle textures, it investigates some techniques that I’m using there that are non-traditional – like, there’s a circular bowing passage where they basically play like writing a circle with the bow on the strings, and that creates this swirling overtones kind of sound. Yeah, I was really trying to stretch myself to find new ideas with the quartet for that piece. And that was partially a response to Aheym being successful in a very particular way, and I wanted to open up the quartet to some other types of sounds that would be coming from me. So that was that. And then– should I keep going?

MD: Yeah, please do – you’re doing great. [laughs]

BD: Little Blue Something also has a story behind it. That one is inspired by two musicians from Prague named Vojtěch and Irena Havel, and they have been quite influential for me. They’re like period musicians, meaning they were trained in Early Music, Renaissance music and they play viola da gamba, and for my style of string writing, this is music that I heard when I was in college. My sister, who’s three years older, had been living abroad and heard them in Copenhagen, and she was a modern dancer and choreographer, and she bought their only LP which is a record called Little Blue Nothing, so that’s where that title Little Blue Something comes from. It’s basically this very strange kind of folky minimalism that they write and improvise with on gambas. And they’re almost like little rounds, so they play these seamless canons or rounds with each other that are in a way very… they have an Eastern European folk thing about them, but also kind of a minimalist element, and it’s referencing in a way the period music which is their background. And for years I had a group called Clogs, which was quite influenced by the Havels. The Havels are very unknown, very small; they gave concerts in Eastern Europe and haven’t travelled much. But it was just music that I found very personal and interesting. I tried for years to contact them, I even went there and never found them. But then in about 2006 I finally – I think somebody made them a website, and I found them through that and brought them to America for the first time, we became friends. So this piece was a kind of dedication to them partly, and also connecting my worlds, because I saw something in common between them and Kronos actually. That piece has two quotations with two cello solos, one at the end and one in the middle, that are taken actually– Vojtěch is the one who plays some of the more soloistic stuff, those are kind of quotes of him and the rest of the piece is my own music but it’s meant to be kind of taking off from this record that they made. That’s the story behind that one. The style of it, I would say it’s a little closer to Aheym in a way, since it was written almost to act like a prelude to Aheym, so that Kronos could have a second piece to put before it.

Listen to Little Blue Something from Aheym here:

MD: Alright, so we’re onto the fourth track, Tour Eiffel, right?

Yeah, Tour Eiffel— that piece was actually commissioned by the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, for this amazing… it’s fifty young singers here in Brooklyn, it’s an incredible youth choir that’s based here, not so far from where I live. They’re really almost like a professional level group, where they sing with the New York Philharmonia a lot, and it’s children who train from an early age and then the choir you hear on the recording is the concert choir, and those are, like– I think it’s actually 48 voices, and they’re ages 14 to 17. So a friend of mine, another composer named Nico Muhly, who’s become quite an important young American, and he’s a close friend of mine, he was doing a project with the youth chorus and asked me to write them a piece for that concert. That piece is Tour Eiffel that you hear on that record. Basically I wanted to write something that would be challenging but also fun for them to sing. The piece is really all about the poem that I set; it’s a really interesting and beautiful poem. It’s by a guy named Vincente Huidobro, and he’s a Chilean poet from the turn of the century, so he was actually the poem was written– he was Chilean but it was written in French. So what I set, they sing it half in French and half in English. Essentially what it is is a kind of playful, almost surrealist take on the Eiffel Tower shortly after it was built. So it starts, the first line is “Tour Eiffel Guitare du ciel”—I lived in France for a while so I’m a French speaker, which is fun, to have the kids sing partly in French, a beautiful language to sing – and that’s “Eiffel Tower, guitar of the sky”. And it has that almost childlike feeling to the text, but then there’s things like these little ominous references to modernity that’s coming, that was maybe symbolised a little by the Eiffel Tower, things like telegraph antenna and the electric wind. And so it’s just a beautiful poem, so I set that and I wrote the music– in a way it’s a little bit closer to what I might play myself on the guitar, so it starts with a kind of guitar figure, this sort of hypnotic thing in 7… I didn’t want to write something too difficult for them or too thorny, so it has almost like a warm, beautiful tone to it. And eventually it ended up becoming this real kind of virtuosic thing, where the choir loved the piece because it really features what they do well. And then Kronos love working with children so I decided to add them to the piece, and David really felt strongly it should be part of this record, just to have something featuring kids, and it is musically different from the other pieces. So that’s the story behind that.

MD: I get the feeling that a lot of the influence or the end result of your composition is determined by who you think is going to be performing it, or how it’s going to be translated musically. Is that always in the back of your mind when you’re writing?

BD: Yeah, I always need something to go on. For the most part I have my agenda musically, but I think I do really like writing for specific people, even if it’s an orchestra. You know, I’ve written orchestra pieces where I try to learn as much as I can about them; I’m writing a piece for the Los Angeles Philharmonic actually, and they have an amazing music director and they’re one of the best orchestras in the world – it’s about getting inside what people do well, what would challenge them, what do they like doing. I wrote a piece for a chamber orchestra in Amsterdam called the Amsterdam Sinfonietta, and they told me they had the best bass player in the world, so I wrote a really really hard bass part. [laughs] I thought, ‘Better give him something to play’. So yeah, you’re right. When I’m writing instrumental music, it really helps to have something to go on, whatever gets the creative ideas going. And often, especially in the case of Kronos, them being such a legendary and kind of storied quartet, it really helped me to have that as a basis for what I was doing.

MD: And does that mindset continue on with your work with The National as well?

BD: In that case it’s more about what works for our singer to sing over, and what– you know, my brother and I write songs for him and he’ll surprise us with what he’ll be drawn to, but we try to really think about, not just what would work for him to sing over, but what would push him to a different place, as far as developing what he’s doing, what we’re doing, it’s a combination of things. But it’s a little less… obviously that’s music that I’m playing myself, as opposed to writing for other people. But there’s a little bit of that. You’re right that, with all of this stuff, it’s not just about what’s comfortable, it’s what’s challenging and what would be exciting and what would be different. I guess that’s kind of the mission with all of these things.

MD: And I know that you have a Masters degree in music that you got at Yale. How much does that influence you and come into play with the music that you’re making now, which is obviously quite a few years later?

BD: Weirdly, I think, it kind of whet my appetite for all this stuff, but I really kept learning. I finished Yale when I was young, I was 22, and I was playing classical guitar and writing chamber music mostly, featuring the guitar in some way. And I think in my 20s I just got lucky where I was able to be in the room with some incredible musicians, people like Terry Riley or Steve Reich, and even younger composers like David Lang and performing with various ensembles, and it was kind of a trial by fire. Guitarists are not typically the best chamber musicians, but I had a lot of experience doing that just by playing concerts and by rehearsing and spending… I spent really the better part of 10 years just learning. And then eventually when I hit age 30 a lot of new things started coming out of me. I think playing in a rock band and having so much experience of that world and travelling also opened me up to thinking differently about music and about what kind of music I might compose. So yeah, it’s been partially [that] Yale sort of opened maybe something in me, but I think primarily my education happened later, actually.

MD: It sounds like you have a lot of stuff going on. Is it difficult to balance that stuff or does it all tend to kind of come together naturally?

BD: Right now I’m busy because we have the band on tour obviously. Usually what happens is we go through cycles of really working a lot on the band and then we’ll have a couple of years off, and that’s typically when I do a lot of the composition work. It seems like I have a lot of balls in the air, but in actual fact I consider myself to be the same musician wherever I go, it’s not that I suddenly come home and put on my classical cap or whatever. It’s all part of who I am and I don’t know that I could live without either things.

MD: It sounds like you’re living a charmed life. [laughs] And I know you’re going to be here in NZ in February, so a lot of people are looking forward to that.

BD: Yeah, it’s exciting.

A short film has just been released for the track Tour Eiffel. Passages, directed by Poppy de Villeneuve and Alex Braverman, serves as the visual accompaniment to Bryce Dessner and Kronos Quartet’s “Tour Eiffel”

Tour Eiffel was composed for the 40-plus voices of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus and is a setting of a poem by early 20th-century Chilean Poet Vincente Huidobro, writing about the Eiffel Tower shortly after it was built. The track includes Dessner on guitar as well as Kronos Quartet and the chorus. “Upon hearing ‘Tour Eiffel’ we imagined ourselves hurtling at great speeds towards an unknown destination,” the directors explain. “Inspired by the line within the song from Vicente Huidobro’s original text, ‘My little boy to climb the Eiffel tower,” we wanted to tell a story of fathers and sons. We travelled with Kim Sanders a retired Dallas Homicide detective, as he took a quiet solo road trip from his home in Texas to the Grand Canyon; a trip he had wanted to take with his son Skipper before his untimely death six years earlier. The resulting film is a rumination on motion, connectivity and loss—a linear journey through space, feelings, and the passage between spiritual realms.”

Watch Passages here:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbbWoFThbYk&w=560&h=315]

- Challengers – Dir: Luca Guadagnino (Film Review) - April 24, 2024

- Civil War – Dir: Alex Garland (Film Review) - April 9, 2024

- Pearl Jam – Dark Matter (Monkeywrench/Republic) Album Review - April 1, 2024