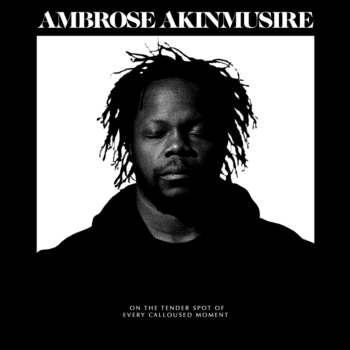

Interview: Trumpet Player Ambrose Akinmusire Talks About His New Album, Released Today

Releasing on Blue Note today is Oakland-based trumpet player Ambrose Akinmusire’s 5th album for the label, On the Tender Spot of Every Calloused Moment.

The 13th Floor’s Marty Duda spoke to Ambrose just a few days ago to get his thoughts on what is going on in his neighborhood with the recent BLM demonstrations and to discuss the making of his brilliant new album. Here is a transcription of that conversation:

M: How are things in Oakland today? I know it’s been crazy over there.

A: I think it’s crazy everywhere in the world. It’s been good and also very turbulent right now.

M: How are you feeling about all of this?

A: In terms of what?

M: Well, first in terms of your own safety, but overall, is this a move in the right direction? Do you think actual change is going to happen?

A: I don’t know. I don’t feel that different, I don’t think that this is new for anybody who experiences it. I think it’s new for everybody else who was either in denial or just didn’t know about it. But if you go back to my albums, I’ve been talking about this since I’ve been recording music. I think ten years now, but it’s just a constant state of life for anyone who’s African American. So yeah, this time isn’t new, it’s just that other people are joining in to the rally call.

M: Looking at it from down here in New Zealand, everyone is suddenly paying attention to this issue, whereas, it’s just been swept under the rug for so many years.

A: I think the key point is that everyone, and we have to look at who everyone is, I think it’s now that everyone really just means white people. Because black people have been saying it for a very long time in a way that isn’t recognised. I mean, the Black Panther party was started in 1966 here in Oakland. That’s a long time ago.

M: I just watched a documentary about Huey P. Newton and they were protesting when he was arrested and put into jail and the things that the folks in the Panthers were saying on camera were almost word for word exactly what I’m hearing on CNN everyday today, it’s amazing.

A: There you go, exactly. And every black person knows that and has known that.

M: Back then, and I’m old enough to remember when that was happening originally in the sixties, that was considered outrageous and very revolutionary and dangerous, whereas, now it’s almost become the norm.

A: Yeah, well now it’s become the norm but especially for someone like myself who was born and raised in Oakland, it’s always been the norm. I can remember when Geronimo Pratt, other Black Panthers got out of jail, I remember going to parade with them. Some of my earliest musical mentors were ex Black Panthers so this had been in my life for a very long time in a very tangible way.

M: Now the album, On The Tender Spot Of Every Calloused Moment, is it now being released this week instead of the previous week? Did it change the release date?

M: Now the album, On The Tender Spot Of Every Calloused Moment, is it now being released this week instead of the previous week? Did it change the release date?

A: Yeah they changed the release date in supposed solidarity with the protesters.

M: Oh, I see. I’m trying to keep track during the whole lock down period, things are moving back and forth all over the place and it’s very hard to keep track of things, but I’m glad it’s coming out finally.

A: Yeah, it comes out Friday. Yeah, me too man.

M: So how are you feeling about the overall having this album being released at this time in what’s going on in the States?

A: Again, I think I’ve always released albums within police brutality in other things that are being protested today. So again, the environment is the same. Pretty much the same, it’s just that there’s more people on the streets and there’s world-wide protesting going on and I think that may be a first, to have a whole world protesting black injustices. I don’t think that’s ever happened. So that’s new and I think that’s beautiful. It feels a little bit more optimistic.

M: It feels like something could actually happen and change this time.

A: Sure.

M: Getting into the nitty gritty of the record, I read that a certain trombonist by the name of Charles Greenlee is an influence of yours? I’m unfamiliar with him so I’m hoping you can tell me about that and how he has influenced what you do?

A: He’s not an influence of mine, it’s just that Archie (Shepp) quoted him, a conversation that he had with him years ago in talking about me.

M: Right. And of course Archie being Archie Shepp who’s written the liner notes, what is your relationship with him?

A: Of course I’ve been influenced by him socially and politically. He’s also been a mentor of mine because I’ve gotten to play with him a few times in recent years, and I’ve interviewed him for a couple of projects that I’ll be coming out with in the next few years. So yeah, he’s just a master that I hope that I can follow, whose footsteps I hope I can follow.

M: Right, well I mean, obviously jazz had an amazing legacy and to be someone in your situation in your age and in this time, does that bear down on you when you go to pick up your horn and blow? Do you think about what’s come before you?

A: I do and I would like to offer a different image. It doesn’t bear down on me, if anything it lifts me up. It’s just like an energy it’s like roots from the bottom lifting you higher and higher, it’s the foundation. So yeah, I really feel great that I’ve been able to stand on the bottom, figuratively, I’ve been able to stand on a lot of their shoulders. But it really does feel like it lifts me, especially to see someone like Archie still out here preaching through his horn and also in written text and in interviews and things like that.

M: Fantastic. I’ve read that you consider this album kind of a study of the blues. Obviously it’s not a blues record, it’s very much a jazz record. Maybe you can kind of elaborate on that concept.

A: I don’t know if that is obvious. Because that’s the whole thing, like what is a blues album? Does it have to be B.B King and Muddy Waters? Because they don’t exist anymore so are we saying now that the blues is dead? Do we have to go back to these albums that were created in the fifties and sixties to experience the blues? I think that the blues is always changing, just like swing, the concept of swing is always changing. So I think that this is very much a blues album in its feeling. It just adds my existence and most, no I’ll say all, African American males living in America’s existence, is one where you are consistently living in a state that is directly related to the blues. So on this album, I’m trying to figure out how to express that in a modern context in 2020. What does it really sound like? You know, the blues back in the day in the Deltas sounded like the Delta, it sounded like Mississippi and sounded like the sounds in that region and the stories in the region, what does the blues today sound like in 2020 of someone who’s born in Oakland? I really think about that and I’m really trying to focus on the solutions, the resilience part, but I’m gonna get me a new baby tomorrow type thing.

M: It’s interesting cause I’ve just interviewed a seventy year old blues guitarist Joe Louis Walker and he has a bunch of different guests, and that’s very much in the kind of quote unquote traditional blues, I mean you kind of know what it’s gonna sound like before you even play it. Not that it’s a bad record or anything, it’s a great record, but it’s nothing that I hadn’t heard before, whereas, like you say, what you’ve done here on this record is definitely not in that vein at all.

M: It’s interesting cause I’ve just interviewed a seventy year old blues guitarist Joe Louis Walker and he has a bunch of different guests, and that’s very much in the kind of quote unquote traditional blues, I mean you kind of know what it’s gonna sound like before you even play it. Not that it’s a bad record or anything, it’s a great record, but it’s nothing that I hadn’t heard before, whereas, like you say, what you’ve done here on this record is definitely not in that vein at all.

A: I offer the opinion that blues is the sonic representation of an experience, of a shared and collective experience and then I argue this to say that the experience that someone like Muddy Waters or B.B King faced in Mississippi, is not so different from one that I face in 2020 in Oakland, cause shit hasn’t changed for black people.

M: I can understand that. And you recorded the album in Brooklyn is that right?

A: I did, I recorded all of my albums as a leader at the same studio, my favourite studio called Brooklyn Recording.

M: So you feel very comfortable there? And of course you have the same pretty much core band that you’ve been working with for like a decade so obviously there’s a communication that goes on between you guys and possibly even with the studio. How does that change or stay the same as you work within that environment?

A: I don’t know how it changes, I’m more focusing on the comfort of it all, the famliness of it all. I like coming together and not having to talk about something that can be so daunting. Sitting in front of these mics and recording something that could, and probably will be, here forever, that is very daunting you know? So I like to have the same, go back to the same, it’s like going back to your grandmother’s house, there’s something about that. Just that comfort that you feel, you feel very comfortable being yourself and talking about whatever. So those things are really important to me and that’s why I’ve cultivated the band that I have, that I’ve cultivated. And, I try not to change the recording process too much.

M: So with the band members, how do you present your music when you’re ready to record to them? Do you give them an outline of what you’re doing, chord changes? Or how much improvisation is involved in that or is it very labeled out for them?

A: That’s a great question. I don’t get too many questions about process unless I’m talking to musicians, then it’s only process.

M: I’m not one of those unfortunately.

A: I do write out all of my compositions. But from there, once I bring it to the band I would say ninety eight, ninety nine percent of the time it’s up to them to interpret it however they will. And that can be tempo, that can be their interpretation of a symbol, a chord symbol or their phrasing of a melody. I won’t say too much because, like I said, like you said, we’ve been together for ten years and there’s a real love. It’s just like having friends you know? There’s a certain trust that you have with them to do the right thing.

M: That’s an interesting word that’s been coming up a lot in the folks that I’ve been talking to lately about making music, is the trust between the musicians within each other so that they can actually do what they feel like they need to do.

A: Yeah, I mean, especially when you’re dealing with a creative, improvised music. You have to trust so you can get to the state of non-judgment. And I think you can’t really create something that hasn’t been there if you’re judging it as you create it.

M: That’s true, very true. Now, most of the album is instrumental, except there are some vocals on one track Cynical Sideliners. So maybe what you could touch on is Genevieve Artadi is that her name?

A: Atrtadi yeah.

M: Tell me a little bit about her and about how you worked her in to what you’re doing on this record.

A: She is someone I’ve known for years when I was in the Monk Institute of Jazz in Los Angeles she was around LA and we have a lot of mutual friends and I’d been hearing her voice in my head for many years and it just never worked out. Because I’d been to the recording session, I recorded the four solo Rhodes things with her in mind and then I sent it to her and we talked about a subject matter and she wrote those lyrics. She did it so quickly, it was amazing.

M: It sounds very nice and the Rhodes is kind of like a good counterpoint to the trumpet I guess.

A: Exactly.

M: Trumpet wise, obviously there are incredible trumpet players in the world that go back for many, many years. Do you draw from that legacy? Or do you try to set that aside so you can do your own thing?

A: No, I always tell people that I’m trying to go backwards and forwards at the same time.

M: That’s great.

A: Yeah, and checking in with myself daily just to make sure that I’m ok while doing that. This morning I was listening to Freddie Hubbard and right before you called, I was listening to Don Cherry with Ed Blackwell. So yeah, I’m always checking out the masters and while at the same time, allowing the spirit to come to me, through me so it can express myself and a bigger, sort of universal consciousness that is music.

M: Obviously you haven’t been doing any live performances recently because everybody’s locked down and there’s no crowds allowed, but when you do play out, what kind of crowd do you attract?

A: It’s all over the board. I mean, from high school students to older generations like seventies, eighties. It can be anything, all races, all ages.

M: Does that reflect the state of jazz these days? That there’s a wider girth of interest in it then maybe there has been twenty or thirty years ago?

A: Twenty or thirty years ago. I don’t know, that’s hard to tell. I don’t know, when I look in the pictures, when I look at photos and things from all the previous generations of jazz, I do see some sort of diversity. I mean, maybe not as much during segregation here in the United States, but post segregation, yeah I think it’s always been diverse, there’s always been a young crowd and that’s how we get young musicians and there’s always been an older crown to buy those tickets.

M: Exactly. And I believe, or I understand that you got involved in jazz at a fairly early age so I guess you’re kind of part of that whole ongoing thing.

A: Yeah. I think everybody’s always talking about jazz and shelf life…. is it dying? But you know, I remember talking to Herbie about it and he said man, people have been saying that since I was young.

M: It’s kind of the same with the blues as well isn’t it? The blues and jazz both get those kinds of questions all the time.

A: I mean, that’s also a point that I’m trying to make on this album, is that it’s not that these things are on the verge of dying, it’s that they’re ever evolving. Not everything dies, some things just evolve and I think that’s what jazz does and has done and continues to do. Music is always doing that. It shouldn’t have to be referential for people to recognise it.

M: When you think about composing and when you’re planning on recording, are you thinking about music all the time or are you thinking about how you can come up with something new or pushing yourself a little bit? What is your mental process like?

A: No, I’m just doing and trying to deal with all my morals and the technical parts of the instruments and ego and all that stuff away from the process and then when I’m in the process I just do. I just write and I just play because there’s nothing else that you can do in the morning to be greater or to be more humble or any of that.

M: Has your relationship with your trumpet changed over the years?

A: Yes it has. Because the way I came to the music was kind of like through a, if we’re talking figuratively, if we’re looking at a house, I kind of came through like the bathroom window. I didn’t come through the front door, meaning I didn’t have a teacher to show me technical things but I did have mentors who taught me about the history of the music and the more personal and intrical things of the black art form in a social context. That’s how I came to music. So I feel alright to say that at a very young age I wasn’t a very good trumpet player.

M: Well, it takes a while to get good at it.

A: I mean, definitely. But I grew up with a lot of great trumpet players around the area. There were people that were really playing. And then I went to college and I got lucky and I had of the world’s greatest trumpet teachers, Laurie Frink, and she pretty much taught me how to, how do I even say this? Yes how to become a good trumpet player, but from a pedagogical standpoint, how to teach the trumpet aside from jazz and creative music. And in doing that, she taught me how to teach myself. So I’ve become a very good trumpet player in my eyes and I feel like I can now express not only the beautiful side of the trumpet, but the ugly side of the trumpet and I can do it pretty much whenever I want to and how I want to.

M: Because I noticed that in the album, there are bits where the trumpet is just squealing or there’s almost a sense of confusion about what’s going on and that’s part of what you do I guess.

A: Yeah. You have to have the ugly with the beautiful. Each highlights the other one right?

M: Right. Here in New Zealand we’ve just gotten out of the whole coronavirus thing and we’ve pretty much beaten it.

A: Yeah, I’m so jealous man.

M: Yeah, sorry about that. But when you’re able to get out there and do your thing again, have you got a plan in mind?

A: Yes, I have a bunch of tours booked for next year, I even have something in September, I don’t think I’ll be doing that but I have some things and I have some artists and residences. Yeah, I’ll be ok when this thing is lifted.

M: Excellent.

A: And I will be an even better trumpet player by then because I’m practicing a lot.

On the Tender Spot of Every Calloused Moment is released today on Blue Note Records.