Good Vibrations – My Life As A Beach Boy – Mike Love (Book Review)

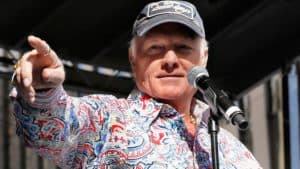

Mike Love tells his own jaundiced version of his legendary, raucous, and ultimately triumphant five-decade career as the front man of The Beach Boys, the most popular American band in history. His own story has never been fully told, of how a sheet-metal apprentice became the quintessential front man for America’s most successful rock band, singing in more than 5,600 concerts in 26 countries.

Pop music has had its fair share of villains and rogues over the years. Some have been in management, like Leonard Cohen’s embezzling manager Kelley Lynch. Then there are the evil genius producers like Phil Spector. There are plenty of dastardly company executives. Then there are a select number of musicians who’ve gone bad. Like Chris Brown, Gary Glitter, James Brown. There’s been the ‘rock star’ bad boys like Axl Rose, Keith Richards, Nikki Sixx and Tommy Lee Jones, etc. But there’s a special place reserved for Beach Boy Mike Love. For over five decades he’s copped the blame by fans and critics for trying to clip the wings of his cousin and the band’s free-spirited songwriter Brian Wilson. It’s been well documented how he interfered with Wilson’s creative freedom and desire for experimentation well before Pet Sounds and potentially why Smile was initially abandoned. Some even try to draw a direct link between Love’s behaviour and Wilson’s breakdown and eventual withdrawal from music during the early 1970s.

Now, 51 years on from the release of Good Vibrations, possibly the group’s greatest masterpiece and definitely the template of many of their most recognised hits both Brian Wilson and Mike Love have put pen to paper to try and explain those heady times and what came after. Wilson’s second bio has the most modest title: I Am Brian Wilson: The Genius behind the Beach Boys (Coronet) is tantalising but in the end short on facts and details. His brothers Dennis and Carl are, sadly, no longer around to tell their stories so the only remaining credible source on offer is cousin Mike Love. And given that the whole story involves Charles Manson, Leonard Bernstein, Republican fund-raisers, parental abuse, mental illness and a cataclysmic fall from grace, as well as the creation of some of the greatest music of the 20th century, it’s a story that needs to be captured. And fast before anyone else departs this mortal coil.

Now, 51 years on from the release of Good Vibrations, possibly the group’s greatest masterpiece and definitely the template of many of their most recognised hits both Brian Wilson and Mike Love have put pen to paper to try and explain those heady times and what came after. Wilson’s second bio has the most modest title: I Am Brian Wilson: The Genius behind the Beach Boys (Coronet) is tantalising but in the end short on facts and details. His brothers Dennis and Carl are, sadly, no longer around to tell their stories so the only remaining credible source on offer is cousin Mike Love. And given that the whole story involves Charles Manson, Leonard Bernstein, Republican fund-raisers, parental abuse, mental illness and a cataclysmic fall from grace, as well as the creation of some of the greatest music of the 20th century, it’s a story that needs to be captured. And fast before anyone else departs this mortal coil.

From a creative viewpoint, Mike Love is not the kind to give you pretty or even purple prose. This is not an ethereal collection of waffle and half-truths like Morrissey’s or a work of drug addled and deluded fiction like Marilyn Manson’s. His is a straight-shooting account. What you see is what he gives you. Believing it is up to you. Mike Love was the College jacketed “jock” of the group, more interested in sports and moneymaking than complex chord changes or being liked by the critics. He lacked the sensitivity and virtuosity of his cousins, but he was a team player back then and they harmonised together from an early age. As the captain of the school’s cross-country team captain, he thinks of his younger self as “renegade … a peacenik and a badass … I sent the message: don’t mess with Love”. That’s a completely different approach to the usual musician’s approximation of themselves at that age. Read most bios and the artist will describe themselves humbly or as a ‘skinny waif, with low self-esteem and an obsession for music as an escape from the reality of their pathetic existence. Or words to that effect. Mike, on the other hand was full of himself, it appeared. There’s little evidence to tell us different though.

Mike grew up in his own private ‘Riverdale’. The Wilson brothers were the Archie Andrews and Jughead, living in the working-class district of Hawthorne (LA). Mike Love was more like Reggie or Veronica, smugly growing up in a large house with a pool, sundeck and five bathrooms – all thanks to his father’s Sheet Metal empire. He started his working life as an apprentice in his Dad’s shop. But when the family fortunes dived dramatically in the early 1960s the family lost their home, leading to a keen sense of thrift. That probably contributed to Mike’s ongoing conservative approach to life, including to creativity and taking risk in the music business.

Mike grew up in his own private ‘Riverdale’. The Wilson brothers were the Archie Andrews and Jughead, living in the working-class district of Hawthorne (LA). Mike Love was more like Reggie or Veronica, smugly growing up in a large house with a pool, sundeck and five bathrooms – all thanks to his father’s Sheet Metal empire. He started his working life as an apprentice in his Dad’s shop. But when the family fortunes dived dramatically in the early 1960s the family lost their home, leading to a keen sense of thrift. That probably contributed to Mike’s ongoing conservative approach to life, including to creativity and taking risk in the music business.

Back in the 60’s if a jock were thrown into the heart the cultural revolution, more often as not he would either become a hippie or shun the whole thing and turn squaresville. At least that’s the theory. Initially Mike smoked dope along with his bandmates but later became an anti-drugs advocate. In 1970 he fasted for three weeks. He tells us he lived on juice, tea and water, and as a consequence, became very ditsy and light headed. One time, the book says, he was arrested after running several red lights in this state and ended up in Edgemont psychiatric hospital in a straitjacket.

Like Harrison and the other Beatles, he became obsessed with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, whom he met in in Paris in 1967 (there’s a big scene in the book alongside a bit of photographical evidence). But unlike the Beatles, he stuck with it. In a recent interview to Portland Tribune, Mike revealed his secret source of vitality. “It gives me rest and relaxation in pursuing activities and combats fatigue,” the singer-songwriter said. “It gives you a sort of high without having to resort to alcohol and drugs. That’s been a big benefit to my life.” That dedication was initiated when he took time out in the early 1970’s to study an advanced siddhi meditation programme, a three-month stay in Switzerland following a three-month stay in France. Since then he’s practiced every day, for 45 years.

The band’s fortunes have been something of a roller-coaster because of the creative clash. Although they were hailed as the best group in the world by Melody Maker readers in 1966. That was ahead of the Beatles, though not for long. Counterculture was turning heavily against them after the non-appearance of the troubled Smile album and then the withdrawal from the Monterey Pop festival in 1967. Plus, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were exploring rock’n’roll as a subversive medium. The Beach Boys were still sing “boop-deboop” numbers about love and cars and beaches. All twee and eventually very passé. It was a crown that fell hardest and furthest: In November 1966, they were No 1 in the US and the UK with their Grammy-nominated “Good Vibrations” but by Thanksgiving 1969 they were playing the Corn Palace in Sioux City, Iowa, to just 50 people.

The dissension in the ranks appears time and again in this book. Mike is brutally honest about Wilson’s ‘flaky Smile project’ with had the inspirations of Pet Sounds but was missing the catchy tunes and impact. In other words, the formula was compromised. What’s also interesting is the lack of detail – and praise – Mike gives to the Pet Sounds project. In the scheme of things his column inches are pretty small. Given this was the band’s greatest critical success, that’s a bit of a let-down. His first reaction on hearing the backing tracks was to warn Brian Wilson (famously) “Don’t fuck with the formula”. “It’s the most famous thing I’ve ever said,” he writes, “even though I never said it.” Apparently. Yet he claims to have written the verses for Good Vibrations on a crosstown car journey, dictating them to his wife without missing a beat. It is plausible that he wrote the leering lyrics to California Girls, and he is proud to have added the “round, round, get around” intro to Brian’s otherwise finished I Get Around, but I think the jury’s out on his claim that he was responsible for the lines “I love the colourful clothes she wears /and the way the sunlight plays upon her hair”? Somehow this seems more like a Brian moment. On other occasions, though, he dismisses critically acclaimed but less commercial Beach Boys records, such as the Love You album (1977), as “weird”.

On the verge of splintering into various solo projects after the 1973 album Holland, the Beach Boys were rescued by Mike, he claims, when he took hold of their live shows and turned them into flag-waving rallies of patriotic nostalgia. They attracted Presidents and conservatives from all quarters. There’s even a couple of photos with Mike standing with Bush senior. Whether intended or not the Beach Boys shows were all about the America that Trump promised to make great again. Bet he never saw that coming.

For Mike Love haters, it should be remembered just how young the Beach Boys were when they were thrown into the spotlight by the surf music craze. It is really like comparing the careers of Mickey Rooney and Shirley Temple to the modern actresses today. They were far more vulnerable and naive. The youngest member of the Beach Boys, David Marks, hadn’t even turned 14 when they had a hit with Surfin’ Safari in 1962.

Mike touches on a few sore points in the book. Like Dennis Wilson, who slept with Mike’s first wife, ending their marriage, and later married one of his daughters. Mike claims that Dennis and Carl both supplied their bed-ridden brother Brian with cocaine and heroin through the late 70s. That would seem pretty incredible, had we not known that that Dennis and Mike’s estranged wife had hired Susan Atkins, a Manson gang murderer, as a babysitter. And yes, there are plenty more of these fiery vignettes in the book.

Good Vibrations is inevitably the only title Mike could have chosen but it runs counter to the competitive, score-settling spirit of this frequently bilious autobiography. If his public persona is that of a peace-loving peddler of wholesome America and summer fun, his private side is so much more much angrier. And although he writes extensively how Transcendental Meditation has kept him calm and grounded it hasn’t entirely soothed the all the bitterness of the Beach Boys’ history. But it has, he writes, kept him from killing people. Just as well.

Tim Gruar

- Civil War – Dir: Alex Garland (Film Review) - April 9, 2024

- Pearl Jam – Dark Matter (Monkeywrench/Republic) Album Review - April 1, 2024

- Blonde Redhead – New Zealand Tour 2024 - March 14, 2024

August 7, 2017 @ 7:41 pm

Hey,great review here,Tim.I kinda used Marty’s voice in there , his cadence and ;lo and behold,it’s you.

Having explored T.M. myself twenty odd years ago aand been to Rishi Kesh three times ,I do get it.His persona is this bitter twisted little man(is he an Aries?) arrogant…i’ll probably go get it out of the public library just ’cause i love bios