Al Anderson (The Original Wailers): The 13th Floor Interview

Reggae Royalty, Jamaica’s THE ORIGINAL WAILERS featuring Al Anderson return to NZ this month for one exclusive show at the Powerstation. The Original Wailers will be performing the iconic Bob Marley & The Wailers album Legend in full, plus a special encore of the Greatest Hits album.

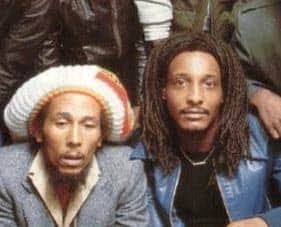

Anderson has been a session musician and band member in a whole host of groups over the years including Peter Tosh, Black Uhuru, Lauryn Hill, Ben Harper, The Centurions, Traffic, UB40, Bad Brains and the Rolling Stones plus many more. Tim Gruar had a chat to Anderson about being in the Wailers, Bob Marley and touring New Zealand in 1979.

I well remember meeting Dalvanius Prime. He’d just made Poi E and was speaking to a group of student radio DJ’s, including me, about musical influences. It was the mid 1980’s. The biggest influence on Maori, he argued was Bob Marley’s tour in 1979. He argued that this man gave rise to political movements and spawned like Aotearoa, Dread Beat and Blood and Herbs.

On the phone from the US, I talked to one of the original touring artists on The Babylon by Bus Tour concert tour. “I love your Maori people, they were so friendly and so hospitable. I’ve been back a few times and every time I learn more and more about the culture. I follow, from a distance, the land rights, Dame (Whina Cooper) and the marches (Hikoi). They gotta stay strong.”

I asked him about what Kiwi bands he knows and he rattles of about 20 names. I catch The Black Seeds, Herbs and Aotearoa but he speaks so fast and furiously I can barely keep up. He is passionate and well educated about New Zealand.

“I can remember the tour. We started in Japan around April and finished in Honolulu. We got to see the whole of the Pacific. Wow. So far away for me and I really love it there, even now.” The tour should have started with two shows in Ivory Coast, he tells me, but was cancelled due to various ‘un-documented reasons’. He won’t say but implies dodgy dealings. But that was all to New Zealand’s advantage he thinks. It meant that we were definitely on the tour. Whilst here, he along with the rest of the band got to visit marae and were welcomed like heroes. It was a profound experience for him. “I was overwhelmed by the support. When we played Western Springs, we couldn’t believe the love.” Sadly, it was Marley’s only tour including concerts in Asia and Oceania, as he died of cancer a little over a year later.

New York born, Berklee-trained Anderson had previously worked with Aerosmith and Stevie Winwood. As a bluesy rock session guitarist in Chris Blackwell’s Island Records stable when he was invited to join a young singer/songwriter named Bob Marley and his band the Wailers. That began a relationship that saw him in the middle of a musical, social, and political movement (Rastafarianism) whose international implications provided experiences satisfying, frustrating, and even life-threatening ‘In New York, we had the FBI tracking us”, he reminds me, when I tell him how Rastafarianism has become popular in New Zealand and how it influenced music here. “I’m glad that it went down well there because Americans, at the time, were scarred of us. They were to ‘square’ you know? They thought we were revolutionaries. We had access to guns and dope and many other things. That’s what they’d claim. We knew Castro.”

I ask him about what he can remember of the early days with the Wailers. “I heard from Chris that Bob wanted a blues sort of sound. He was always trying things and he wanted more than that ‘chika-chika’ sound you get from the Caribbean sound. You know, the traditional sound.” Marley had Nashville musician Wayne Perkins (Bobby Womack, etc) playing on songs like ‘Concrete Jungle’, noted for the memorable guitar solo at a time when reggae didn’t have these. “Nobody’d done stuff like that but I didn’t want to play like that. So, when Bob asked me in he’d had most of the guitar stuff on tracks on Natty Dread already done but needed some more guitar, BV’s horns, acoustic harmonica. He asked me, “What did I hear?” I wasn’t really sure what he wanted. I did a little hard rock and blues guitar. He didn’t really go for that. Chris and Bob didn’t want that sound. So, I’m thinking “I know what they want. They want that sweet blues thing.” So, in the end Anderson played more sweetly for No Woman, No Cry, to give Bob a more tender feel to sing by. ‘Rebel Music’, on the other hand was more aggressive. So Jah Seh was more of a soaring and majestic song “so I tried that. I was learning to play outside my comfort zone, too.” For Anderson, who was already a seasoned player it was one of his hardest sessions ever “because I had to please both Richard and Bob – my Boss and his Boss!”

“At the time, I didn’t know this guy called ‘Bob’. Obviously, I knew who Chris. I’d been in the studio with him. He was picky, his ears guided things in certain ways that I didn’t always agree with.” But then, Anderson says, he was only a sessions man.

Then the Natty Dread tour the turned him from session player to band member. That prompted a trip to Jamaica, where the band was based for rehearsals and writing. “I left my home in England for three years. I couldn’t go back to see my family or even make contact. We lived in Trenchtown (Jamaica) in between. I think people thought I was privileged – but that was Chris, coming from a wealthy family. I had to learn patois, eat Jamaican food.” Anderson reminds me that before Natty Dread was released the band slept rough and poor. “I slept on the floor for a year before they distributed the album.” Bob, he says was generous to a fault. Despite already having three children to raise, he wanted to put up Anderson in a hotel. But Anderson knew he couldn’t afford it, so he chose to live like the locals instead. He stayed in Bull Bay, where Bob had a house with Rita. “I was plagued with mosquitos. A kid from England like me got eaten alive! ‘Bob had a tough time, he says and he knew that to understand the music he had to have a “real tough time”, too. To feel and learn how and where he grew up.”

Anderson has been documented many times for his opinions on the Barrett brothers, who made up the core of the Wailers at the time. “I hadn’t met Carly (drummer Carlton Barrett) or his brother Family Man (bassist Aston Barrett) but I got to know them really well over time.” He says Carly was like the “jewel in the crown” of the band. Funny, a great cook, a real charmer. But Aston was always a bit selfish. Later on, he recognised the split that caused so many divisions in the Marley family legacy.

“Family Man is no leader. (He swears his name). He’s so poorly educated and thinks of nobody but himself…the most selfish of individuals I’ve met. I don’t think Bob liked him because he didn’t leave anything to him. When he was (getting cancer treatment) in Germany. He didn’t come to see him. Bob asked. We all went, even Rita, the band, everyone. He (Family Man) never bothered…. For Family man – it was all about the money. No heart.”

Anderson eventually became very cynical of the Marley management team. He felt that Bob was being exploited by everyone around him. It started when he first joined the band. He felt like an outsider. “Peter (Tosh) and Bunny (Wailer) didn’t like me at all because they saw me as this guy Chris (Blackwell) had brought in to break up the band. But that wasn’t the way. Peter became close friends. The ways Bob’s management ran the band wasn’t what I was used to – no contracts, loose royalties, hand shake style participation gratuities. It was all loose and fluid. It was how Bob got taken advantage of and how the royalties for his albums became so murky after he died. Everyone wanted a piece of him.”

Originally, Anderson says, the band didn’t directly receive royalties for anything they did. When they did get cut in, the payment system was not transparent. “You couldn’t see statements. It was hard to know how much the cut was from the original. For me I wanted to play with everyone and I need to plan things out. I wanted to play with Jimmy Cliff, and I did. With him the invoicing was easy. The contract was easy. Not with Bob.”

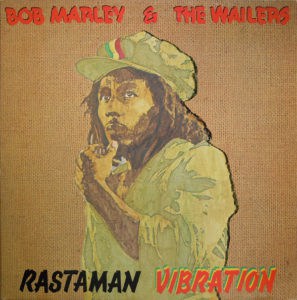

Anderson left the Wailers after Rastaman Vibration (1976) due to managerial problems, he says. “Bob was a great, fantastic leader, and a guy you could talk to about ideas. But as soon as Don Taylor’s new management came along he – well – literally took the crumbs out of our mouths. He had no heart or soul. It was all business. And he was grubby. Cold. And I’d had enough. I was struggling, hurting. I went to work for Peter Tosh. He was an artist and a friend.” “Because for me, and Peter, it was all about the music, until the politics came.” There was a number of incidents where Anderson figures he wasn’t paid properly for tours. “The still owe me $10K for the Legend Tour.”

Anderson left the Wailers after Rastaman Vibration (1976) due to managerial problems, he says. “Bob was a great, fantastic leader, and a guy you could talk to about ideas. But as soon as Don Taylor’s new management came along he – well – literally took the crumbs out of our mouths. He had no heart or soul. It was all business. And he was grubby. Cold. And I’d had enough. I was struggling, hurting. I went to work for Peter Tosh. He was an artist and a friend.” “Because for me, and Peter, it was all about the music, until the politics came.” There was a number of incidents where Anderson figures he wasn’t paid properly for tours. “The still owe me $10K for the Legend Tour.”

Anderson reckons that Tosh could have run for Prime Minister. He saw him as wise. He would work with many who couldn’t read or understand the contract side of the music business, unconditionally. He says that when reggae and Rastafarianism really took off it became an overwhelming and metaphysical experience for them. “Being political on stage was part of the act, you know. But Bob and Peter took it off stage, too. I wasn’t into that.” Bob was a leader, with followers from all over the world, he was close with everyone from was close with Michael Manley to Fidel Castro. “Communism in the Western hemisphere didn’t work. It was a threat, not an ideology. We had the FBI on our trail for being revolutionaries and speaking out about human rights – because of the connections. I left because of that, too. I’d had enough of Don Taylor, the politics. I loved Bob but I wasn’t going to risk my life.” He’s referring to America’s opposition to the connections that were made to potential revolutionary action. “Africa Unite? Cuba Unite? Jamaica Unite? You don’t say shit like that and just walk away from it. There are consequences.”

Finally, we get to the origins of the band. I can see Anderson has been building up to this. There is confusion over the Wailers ‘brand’ with there being several out there, I ask. Peter, Bunny, and Bob are considered the Original Wailers, of which only Bunny is still alive, and not a member of the current band (The Original Wailers). Then, there is The Wailers led by Family Man.

“The word ‘original’ in Original Wailers refers to the original intent,” Anderson says, “it means the original vision of Bob’s band and his music. His vibe, you know. It’s not the original members in a group.” The Original Wailers was formed by Al Anderson and another former Wailer Junior Marvin in 2008. However, has now Marvin departed the band. Despite the name, the band has never included any of the original members of the Wailers. This tour will have all the songs from the Legend compilation album (1984). Marley fans will be getting a veritable smorgasbord of great tunes.

The Wailers Band, led by Family Man (Aston Barrett) is a morph of the original Wailers, with all but Barrett on board. Both bands claim to be the ultimate Marley legacy. Family Man’s last tour was in 2015. Both exist together and apart. Both perform Marley’s songs. Anderson optimistically states that we (the Original Wailers) can “co-exist with those other people (The Wailers Band). I want to to continue with the Original Wailers and reach out to its rightful audience, show people respect and honour Bob. That’s it, really.”

Tim Gruar

The Original Wailers perform at Auckland’s Powerstation tomorrow night (Dec. 14). Click here for tickets.

- Civil War – Dir: Alex Garland (Film Review) - April 9, 2024

- Pearl Jam – Dark Matter (Monkeywrench/Republic) Album Review - April 1, 2024

- Blonde Redhead – New Zealand Tour 2024 - March 14, 2024