Public Service Broadcasting: The 13th Floor Interview

UK band Public Service Broadcasting is known for their unorthodox approach to music-making…essentially they tell stories using old films clips and sampled dialogue often sourced from historical footage. Their 2015 album, The Race For Space, revised the Soviet/American space race from the late 1950s through to the 1969 moon landing.

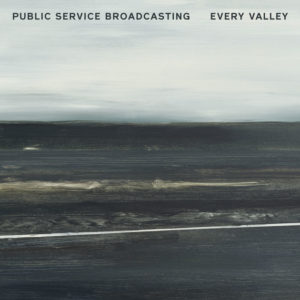

This time around, they take on the plight of the Welsh coal miner, or, as their press release explains, they are “using the history of coal mining to shine a light on the disenfranchised”, on their new album, Every Valley, released today.

Since the previous album, the group has expanded to a trio with founding member J. Willgoose Esq. now joined by Wrigglesworth and new guy, J.F. Abraham.

The 13th Floor’s Marty Duda spoke to J. Willgoose Esq. about the new, expanded band, and about bringing in guest vocalist such as Manic Street Preachers’ James Dean Bradfield and Camera Obscura’s Tracyanne Campbell to add an authentic Welsh voice to the mix.

Click here to listen to the interview with Public Service Broadcasting:

Or, read a transcription of the interview here:

MD: You’ve gone from Space Oddity to Working In A Coal Mine; something along those lines…

JW: Yeah, that was the idea.

MD: And along the way, you‘ve picked up a new member in the band, J.F. Abraham. I’m wondering first if you can talk a little bit about him and his involvement, where he came from, who he is.

JW: He was paying with us on the tour for The Race of Space; so, we were doing it as a duo plus a touring musician – the way you see a lot of bands slowly expand their line-up, I guess; and I always had my eye on expanding things, if we could, because the more musicians that you’ve got, up to a point… the more interesting the show can be – and he just added a lot to it. He’s a great musician. He’s a really good performer, which is something that me and Wrigglesworth aren’t necessarily; so, that helps. He plays the bass for us, but he’s a classical trumpet player by training; so, when it comes to doing all the brass arrangements and string arrangements for the new album, he’s an extraordinarily useful man. It’s just nice to have another person on board, really, so it’s not just me and Wrigglesworth bickering all the time.

MD: How does he fit in with the recording process? Is he part of that as well, or is that mostly just you? How does that work?

JW: Most of the demoing stuff is me: so, I get the demos to read, when we get to stay at home, but there are various things on the demos that don’t necessarily translate into the real world or being played by real musicians; whether it’s handing over drum parts to Wrigglesworth and saying, “Can you actually do this?” or handing stuff over to J.F. Abraham and saying, “What brass do we need for this to get a sound like this?” or, “What would be best for this song?” That’s a big part of translating it into reality, I guess, from the concept in my head, and he conducted all the sessions with the strings and the brass and speech of our language, and I definitely found that it’s really useful having a bridge between your band and the music world proper.

MD: We should talk quite a bit about the substance of the record: a topic which is based around the mining of South Wales and the transformation that that industry went through over the past fifty years, or so. First off: that’s a long way from what you were talking about and writing about before. What brought you to this subject?

MD: We should talk quite a bit about the substance of the record: a topic which is based around the mining of South Wales and the transformation that that industry went through over the past fifty years, or so. First off: that’s a long way from what you were talking about and writing about before. What brought you to this subject?

JW: I think that was one of the attractions, really. It was how much of a left turn it was, and how different it would be from what went before, and not wanting to become predictable or just stuck in this procession of, “What’s the next big engineering or technical or exploratory milestone that we should cover?” and keep everything in our kind of output: in the same vein. I was drawn to mining because I thought something about industrial heritage and industrial decline could be interesting, and I knew the British Film Institute – who we worked with – had a lot of material; and that’s always practical reasoning behind choosing album subjects as well – knowing the footage is there, and we can licence it – and then the more I read about the community, and the more I read about the strength of the community – particularly in South Wales around the time of the strike in the ‘80s – I just thought, “Maybe you could get more out of this album if you framed it more specifically and geographically;” and that’s how it came to be about what it’s about. It was kind of ironic in actually making it about one place: it’s made about that one place, but it also… seems like – even from people’s early reactions to the record – you’re seeing it translate in ways that you wouldn’t necessarily expect, because it’s not just a story that applies to this place; it’s a story that’s repeated all over the western world, I think, in all kinds of different industries.

MD: Right. I grew up in rural Pennsylvania in the United States, and I can relate to you.

JW: Oh well, there you go!

MD: Which is not far from a lot of the coal mining down in West Virginia… and I’ve heard President Trump going on about how he’s going to revive the coal miners, and all that; so, it’s still pretty relevant, I guess. Were you aware of any of that as you were making the record?

JW: You know, it was funny, because I had decided on this in 2015, and it felt like quite a random and scary decision to make, because you’re like, “God! Are we taking too big a risk here? Is anyone really going to care if we make this album?” But the more we got into it, and the further down the road we got, the more things started happening in the real world that made it seem like, “Actually, this is a really good decision, I think,” because it had all kinds of political developments in the UK that are still – I think – traced back to this industrial dispute in the ‘80s, in a number of ways; and you have Mr. Trump on the other side of the Atlantic, talking about bringing coal jobs back…. They’re mining the same seam, I think, in the north east of America, as they are in Wales: it is… literally the same seam of coal; and you start to realise that this is connected and symptomatic and emblematic of something bigger than what you’re just focussing on. It was quite fascinating to watch that develop as we were ‘beavering’ away.

MD: I was reading some of the press material that came with the record, and saw that… you had not played in Wales during your UK tour in 2015, and there was some kind of response to that from Cardiff. Maybe you can elaborate on that a bit.

JW: One of the things we learned about being in a band is: if you want to annoy your fans, the best thing to do is to announce a tour for anywhere in the world. Everybody just starts moaning and says, “Why aren’t you playing here?” Occasionally, you get one person going, “Yay!” and that’s about it. When we announced our UK and Ireland tour for the second album, there wasn’t a Welsh date on there because of the politics of tour booking and promotion: often they won’t let you do Bristol and Cardiff together; and we were doing Bristol and not Cardiff, and just had a lot of very angry Welsh people saying, “You do know Wales is in the UK, right?” and just getting quite irate with us. I think part of the thinking was like, “Oh God! What can I do to make it up to these people; they’re so angry?” I don’t know to what level that played into, “Oh, we’ll just do an album all about South Wales then.” I think I might be overstating that, in retrospect, but I do remember being a bit like, “Oh God! We’ve made everyone very unhappy.”

MD: Well, it’s nice to be wanted anyway!

JW: Yeah! No, that’s true. It’s a far cry from the early days when even the people in the places we were going to were like, “Meh!”

MD: How much actual, on the ground research and meeting the people, and all that, did you do to prepare for the record?

JW: Quite a lot in various stages. We were fitting it around the tour that we were still doing for the last albums. A lot of research took place remotely – whether it was watching films in London or watching stuff on the road or reading stuff on the road – but I went down, several times, to South Wales, and met people at the Big Pit National Coal Mining Museum in July… 2016. I spent a week researching at the South Wales Miner’s Library in Swansea, and just generally ferrying back and forth a little bit, and trying to get a feel for the area, and not just… writing remotely about it, and try and give it more solid roots in the area that we were writing about. It was quite a solid undertaking. Then, when it came time to actually record the album, we spent over a month there, transforming this community hall into a recording studio and setting up home…. It felt like a really important part of making the record, and an appropriate way of making the record.

MD: Were the locals aware of what you were doing?

JW: The ones I spoke to, for research purposes, were, but we tried to keep a lid on everything else during January, February, but there were a couple of little murmurs that started surfacing online: “I hear your in Ebbw Vale. What are you doing there?” We were trying to stay under the radar, but for a band of our profile, staying under the radar is remarkably easy. Nobody really knew who we were or cared. We had this back story prepared that we were this band called The Antennas, and we were just in town to do some recording, and it was our first album; and nobody cared… and we just got on with it.

MD: Listening to the record: it seems to me – and I may be wrong – there’s more traditional music making on this record than the more ‘cut and paste’ and sampled stuff that you did for Race for Space, and you’ve got a couple of guest artists in there. Was that your plan from the start: to approach it like that, or did it just develop?

JW: I think, in terms of the overall sound of the record and the character of the record and the production behind it: I did want it to feel richer and more earthy, and maybe a bit more natural. A big part of the album sound was actually recording to tape for the first time for us, and it made a massive impact on the sound – bigger than I thought it would – certainly on the drums: the drums just sound amazing through tape; and that was me being quite sceptical about all that. In terms of instrumentation and working with guests: I think because some of the archive material that we were hoping to find for some of the subject matter, I just thought some of it won’t exist, or we’re not going to be able to find it and have the same kind of resonance that we would have if we just got somebody to sing it – actually got somebody’s voice on there, and something we can have more control over and we could shape the story and be a bit more adaptable, a bit more flexible in that way – so, that was one of the reasons for going with singers. It just helps you shape things a bit more personally, I guess, because you’ve got more direct control over what they’re saying; and just getting people like James Dean Bradfield on the record, and having him singing a poem from the ‘30s, it had a resonance and a weight to it that you’re going to struggle to match no matter how much archive you go through.

MD: And you have him and Tracyanne Campbell from Camera Obscura. How involved do they get with the actual songs that they’re singing…?

JW: James was very hands on, and he steered me away from a couple of ideas that were – on my part – a little bit ‘ropey’; and he did it very delicately and subtly. He was a big help, and he was very dedicated and very studious, I suppose. He didn’t just breathe in and out, and that was it: he came down, did a demo, went away, thought about it, and was there for

a long time doing his vocals. It was amazing to watch somebody, at that level, working, because he still has that passion and focus that must have been responsible for getting him where he is. Tracyanne was a similar process: I flew up to Glasgow, and we met, and then I flew up again later in the year, and we did a demo recording; and that really changed the way the song was structured. I was writing to her strengths – which is her voice in a certain register; I was trying to work out where it sounds best – and it totally changed the structure of the song. Then she came down to record – and she’s only got one line to sing really, but it’s still quite a technically difficult part – and we just took our time over it; and, again, it’s just great working with a professional; somebody who cares about what they’re doing, and has so much skill and class behind it all. It’s always educational to be involved in that situation with a musician.

MD: The folks I’m interested in talking about, that also appear on the record: they’re on a track called They Gave Me a Lamp. It’s a female trio called the Haiku Salut…. I hadn’t heard of them before, and I did a little reading about them, and they seem fascinating! Maybe you can tell me a little bit about them and why you had them work with you.

JW: I stumbled across them on the internet – they had randomly copied us in on mixed that they had done of one of our songs – and that’s one of the good things about the internet, because about an hour later, I had fallen in love with their music and realised that their sound was, pretty much, the sound that I wanted for this track that we were hoping to do about women’s sport groups, and about this political awakening of a generation of women in South Wales; and we don’t often get the chance, because of what we’re writing about, and because  of the material being very male heavy, we don’t often get the chance to focus on the more female voice, and get a more female focussed subject matter out there. So, when we do, it’s nice to be able to work with female vocalists and female singers and female musicians, to try and progress the balance a bit. I just got in touch with them and said, “This is what I’d like to do. Would you be up for this?” and they said, “Yes,” which is good, and then in the meantime, our visual artist, Mr B, has been spending a bit of time at a few museums, and he’d found this woman – Phyllis Jones – in South Wales, who was a colleague we’d known, and she’d written this memoir, They Gave Me a Lamp; and something about that title really struck home for me, and it really plays into Haiku Salut, because they do this amazing lamp show… where they plug in a load of vintage and antique lamps, and synchronise it all with the music. It’s a beautiful thing to watch. It felt like a good and fortunate ‘co-timing’ of many different things falling into place for this one song; and I think they did a great job, and it was really good to work with them.

of the material being very male heavy, we don’t often get the chance to focus on the more female voice, and get a more female focussed subject matter out there. So, when we do, it’s nice to be able to work with female vocalists and female singers and female musicians, to try and progress the balance a bit. I just got in touch with them and said, “This is what I’d like to do. Would you be up for this?” and they said, “Yes,” which is good, and then in the meantime, our visual artist, Mr B, has been spending a bit of time at a few museums, and he’d found this woman – Phyllis Jones – in South Wales, who was a colleague we’d known, and she’d written this memoir, They Gave Me a Lamp; and something about that title really struck home for me, and it really plays into Haiku Salut, because they do this amazing lamp show… where they plug in a load of vintage and antique lamps, and synchronise it all with the music. It’s a beautiful thing to watch. It felt like a good and fortunate ‘co-timing’ of many different things falling into place for this one song; and I think they did a great job, and it was really good to work with them.

MD: Speaking of titles of things: the title of the album is Every Valley, and my understanding is that you’ve taken it from some 1950s transport film. Does the film itself relate to the record?

JW: Yeah, the film is on the first track and it’s on the last track: it’s the first sample you hear, and it’s the last sample you hear; so, it starts at sunrise, and ends at sunset; and it’s very much, supposed to be, a framing of the album. For a long time, it was an album without a title. I didn’t really know where I was going to go with the title, but something about the way it sounds, ‘every valley’ – I’m really keen on just the way it sounds – but also the message behind it of “It’s not just one place that this happened”. It happened all across this region, and, actually, by extension and extrapolation, you can extend it out all over the world, and say that this happened in so many different ways, in so many different places; and it suggests a kind of togetherness as well – that everything’s in it together – and that really appealed to me. Then afterwards, I found out that the British Transport film, that we’d adapted to Every Valley, was probably named in honour of Handel’s Messiah; so, it ends up looking like we’re really clever… but no, that was a happy accident.

MD: The final track on the record, Take Me Home, sounds like it’s being sung by a choir; is that what… we’re hearing?

JW: Yeah. I think one of the reasons behind wanting to go to South Wales was just being aware of their musical heritage, and ex-miners and ex-steel workers, and still there’s this tradition of male choirs and four part harmonies: it’s such a simple but rich sound. Singing is such a big part of the Welsh culture anyway, but when you get these big, burly blokes – very manly men – but they’re singing this very emotional and rich sound, it’s immensely moving, I found; and it felt right – given the subject matter and given the way we were going about the album – to have them close the album; and they’re singing a song about leaving home, basically, but wanting to come and return, because times have changed. It encapsulated everything about the album, and sends it off on the right note, I think. I find it a very moving way to close things off.

MD: Now that the album is coming out by the end of the week here: are you taking the show on the road, or are you touring behind it? How are you presenting it?

JW: Yeah. We’re playing some festivals in the UK and in Europe over the summer, and then once the big festival road show, over here, winds down in September, we’ll be heading over to the States and Canada for a few weeks, and touring it there – it’d be interesting to see how that goes down – and then back to the UK and the rest of Europe for October and November. Then hopefully, next year, journeying further afield to, maybe, South America and, maybe, a bit of Australasia as well; it would be great to be able to come back.

MD: It must be a very different live experience, because – let’s face it – most shows you go to, the audience is either dancing or singing along, and that just doesn’t seem appropriate for what you do. Is there a bit of unease or tension with your shows?

JW: I think… one of the things you start learning, when you start doing this as a living, is crowds are a funny thing: they change so much from night to night; even if you played two or three shows in the same venue, the crowd can be totally different from one night to the other, and it just brings a totally different atmosphere. We do get shows where people are more respectful, I guess, and because we’re screening wee edited versions of the footage and films that we’ve written around, in time with the music that we’re making, some people will just focus on that, and it almost becomes a cinematic experience for them; and you don’t get a great deal of movement, but then you go to other shows, and people are dancing all over the shop – and it doesn’t matter what you’re playing next, they’re dancing all over the shop – it’s really interesting. As musicians, I think we always like it when we can see when we’re getting a reaction from people, but even when we think the crowd have been a bit quiet, when you get to the end of the show, you normally get this outpouring of appreciation; and you realise that people have been absorbing it all the way along, but they just haven’t necessarily expressing it in the way that you’re used to, I guess; it’s really weird. It kind of goes down equally in a club, late at night, as it does when we played in a Romanian cinema… as part of Transylvania’s film festival; and again, it felt like quite a quiet response, but at the end, people were effusive. You find yourself in some interesting places.

MD: And one of those places, I assume, this time around, will be Cardiff. Are you planning on playing there?

JW: Yeah! Yeah, it’s the opening date of our UK tour.

MD: Smart move!

JW: Yeah, we’re looking forward to that one. I think it should be quite a fun one.