Steve Hackett: The 13th Floor Interview Part 2

Yesterday we brought you the first part of Marty Duda’s recent interview with former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett. Today, it’s part two, in which Hackett discusses his feelings about the various permutations Genesis went through, his favourite contemporary bands, and to start things off, an insight into how he views playing in front of a live audience as opposed to recording in the studio.

Click here to listen to Part 2 of the 13th Floor interview with Steve Hackett:

Or, read a transcription of the interview here:

MD: Is it the kind of music that is a joy to play in front of people and play on stage? Do you find it more satisfying than in the studio?

SH: Well, I love recording, because you can take several different runs at the high jump, and you can edit something until the cows come home, but doing it live in one go its been great, and – as I say – audiences reactions have been just phenomenal; so, it just seems to be snowballing the whole time…. I, basically, love doing it, and living out of a suitcase; whereas, I think, a lot of my contemporaries grumble about that, and that’s not how it is for us: my wife not only writes songs, but she’s made films, and she’s also written books, and she’s an historian, and she wants to know about the history of everywhere; so, there’s not a dull place on earth… you might think this place doesn’t look like much now, but she’ll say, “Yeah, but this was a Roman settlement of two or three thousand… and there was a big river running through the middle of it,” and that’s just around the corner from her family home in Norfolk… and it’s wonderful; so, she’s always bringing me up to speed, not just geographically – she’s got a much better sense of direction than me – but historically as well. She’s very well informed.

MD: Now, getting back to Genesis: you alluded to the various forms that Genesis took over the years – with you and without you – and they seem to be one of those bands that everybody has a strong opinion about, and – like you say – in different parts of their history as well. What was your reaction to the band as it changed and mutated and became different things? Were there times when you were worried about the legacy, or were there times when you were more proud than others?

SH: I think it was the music that punk couldn’t kill. I remember the time when I’d just left the band, suddenly, all of that was very unfashionable, according to the English press; a new broom sweeps clean. I think the band was interesting in all its incarnations; right from when they were starting out – leaving school, or even recording stuff when they were still at school – painfully shy, romantic songs about a girl they hadn’t yet met, and then, I think, that sense of romance spread over into a kind of story telling tradition; so, romance, for the band in the early days, meant Greek mythology. In many ways, the songs were, at one stage, removed. I don’t think there had been enough empiric experience – there hadn’t been enough personal events in their lives – but I found the era when the band emerged in the late ‘60s very interesting: a very interesting time when the two separate strands of music that I was listening to – I was listening to Bach on one hand, and blues on another – and thinking, “These two types of music are never going to come together. It’s never going to happen,” there’s Segovia in one corner, and Jimi Hendrix in another; and then the wall started to come down, and people started to involve, as I say, the pan-genre approach, where all things were welcome: suddenly music was taking on board a jazz influence…

MD: Were there other musicians that were doing things at the same time, that made you feel like it was allowed to be doing that?

SH: Yeah, I think so. I think there were a whole slew of British bands at the time – Procol Harum, Jethro Tull, Yes, King Crimson – who were taking a pan-genre approach. There was the influence of big bands. People were casting an ear to Roland Kirk and John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis; on the other hand, I spent – and still do – a phenomenal amount of time listening to Russian orchestrations, thinking, “How can I get my orchestral work to sound as rich?” … and I think, obviously, The Beatles, the fact that they had George Martin on board as Beatles numbers five and six: I think George was, perhaps, worth two Beatles with his great ability to be both a technical man, to record them in interesting ways, but at the same time, to be old school enough to have done his lessons and learned music from the grass roots up.

MD: Well, they say you have to know what the rules are before you can break them.

SH: I think so, yeah. I think you’ve certainly got to do that, and if not be able to create full character portraits in every one of these yarns, you’ve got to at least be able to sketch, or have an appreciation of those things. I think it’s important to listen to Gershwin, at the same time, to listen to Lennon and McCartney; cast an ear to Borodin, but then check out what all the American blues men were doing as well; not have any prejudice, in other words. I remember when I was twelve years old, listening to Duane Eddy, and every other song I heard, at that time, seemed to be an absolute masterpiece, I was hearing on Radio Luxembourg. Of course, we only really had two radio channels in England, and one was the Home Service, and the other one was The Light Programme. The Light Programme played everything musical, from Mario Lanza to Elvis Presley to Glenn Miller, and that’s just the way that 1950s radio was set up. There was very much that controlled thinking: the State knows best – Aunty BBC. We were being nannied along in those days, and then the radio pirates broke all that; and it meant that, at that time, suddenly you were able to hear Bob Dylan side-by-side with Jim Reeves, and draw tremendous amount of inspiration from both of them alongside The Beatles.

MD: Are there any contemporary artists that you’re particularly enamoured with these days?

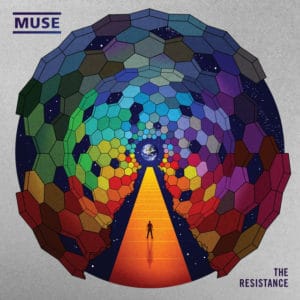

SH: Yeah, I think that, very often, I find myself being interested in what’s going on – different bands like Arcade Fire, Muse and Elbow have got something to offer – but I think the bands that I listen to, tend to be pan-genre themselves – in other words: the Muse album like The Resistance, they’ll wander off in the middle of it to a piece of Chopin – I think that’s all fine; there’s nothing wrong with that…

SH: Yeah, I think that, very often, I find myself being interested in what’s going on – different bands like Arcade Fire, Muse and Elbow have got something to offer – but I think the bands that I listen to, tend to be pan-genre themselves – in other words: the Muse album like The Resistance, they’ll wander off in the middle of it to a piece of Chopin – I think that’s all fine; there’s nothing wrong with that…

MD: I can see where you could draw a line going back, from Muse or Arcade Fire, to Genesis as well. It seems like it’s a natural progression.

SH: Yeah, I think so. I think these bands would have been aware of that – and occasionally, I think Pete’s worked with one or two of them – and it’s nice when those bands mention things that we did at one time – or that I’ve done – I’m thrilled with that. I’m thrilled with the fact that at one point, I remember seeing John Lennon and Yehudi Menuhin arguing on a TV show – on a chat show – and they were poles apart – and I had tremendous respect for each of them individually, but there was real ‘ding dong’ going on, and… I suspect in Lennon’s case, it was class war – but the interesting thing is that Lennon liked what we were doing in 1973, and mentioned this… and then a few years later, Yehudi Menuhin made a film called From Kew to Findhorn Foundation – it’s the story of British gardens – and he used a piece of music of mine, at one point – something that I’d written on Please Don’t Touch – and I thought, “Wow!” All the other pieces are Mozart and Bach, and various things; and there’s these two guys arguing, but I’ve managed to have their attention for five seconds. I think that’s probably the greatest achievement that I’ll ever have, but it might be a little too subtle for most people to get that; but I’m proud of that.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DaQsTXFKFsw

MD: Do you have any contact with any of the former Genesis band mates these days?

SH: Yeah, I do. I sometimes see Pete and Mike and Tony. I see less of Phil, because he lives in the States. We still all talk, but it’s a very competitive band; it’s very strange. Usually, if one of them does something that I like, I’ll phone them up and say, “Oh, I really like your album. That sounds really good.” I do that, and often I’ll publicly say that, but I noticed that the others tend to be much more circumspect: they’ll say one thing in private, but they won’t say anything publicly, because they’re competitive.

MD: Even at this stage; it’s amazing!

SH: Even at this stage! Yeah, I know, it’s extraordinary, isn’t it…? It’s a terrible thought, isn’t it…? But I’m very proud of the stuff that we all did together, and maybe one day, there’ll be a chink in the armour, and some light will be let through; a resignation at some point. It’s entirely possible, and I’m up for it, but I wouldn’t hold your breath! They’re all plugging away. None of them have resigned their commission, really.

MD: In the mean time, we do have the tour coming; so, I’m looking forward to that. I think it’s going to be pretty cool.

SH: I want to honour this past work that I think is a body of fine work, and – as I say – to appeal to the disenfranchised fans, who feel that the band became something else – became a pop group, and sold out; whatever you want to say – and I would say that the band has something to offer in all its incarnations. I think that it became slicker – obviously, it became more commercial – but I think what’s more interesting, is the music that was not recorded to ‘click’ tracks: where we had to really listen to each other and the invisible conductor was working overtime, in terms of… really to feel each other…. It was music that could turn on a dime, and music that’s full of surprises, that welcomes so many things, and not just the storytelling aspect, but social comments, the comedic aspect to it – stretching right back to vaudeville and the music hall – so, it’s in the British tradition. I tend to think that The Beatles were, possibly, Chuck Berry meets George Formby; whereas, I think there’s an aspect of George Formby still in there, perhaps, with Genesis – but, at times, it’s George Formby meets Beethoven or Mozart – Shostakovich: there’s a bit of that, and there’s plenty of big bands as well. European music, but it’s Anglo-American, in a way, as well.

Steve Hackett performs at Auckland’s Town Hall on Friday, July 28th. Click here for tickets.

- New Music Friday: 13th Floor New Album Picks: April 19, 2024 - April 19, 2024

- JessB – Talk Of The Town: 13th Floor New Song Of The Day - April 19, 2024

- The Bacon Brothers – Ballad Of The Brothers(Forosoco/Forty Below) - April 18, 2024